We admit that few of us think, and even more so talking about his intestines. But you may be surprised at the importance of what goes into the intestines and what goes on inside it. This least favorite of all parts of your body is not like a portable trash bin, but a first aid kit.

There is ample medical evidence that diet has a profound effect on health, and new scientific discoveries show us why this is so. In addition, they also show us why supporters of paleodiet and vegetarianism do not understand how our omnivorous digestive system works.

In your

large intestine, most of your microbiome lives - the community of microbial life, living both on you and inside you. In fact, everything you eat feeds your microbiome. And what they produce on the basis of the food you eat can support your health or develop chronic diseases.

In order to assess the human colon and the role of microbes in the digestive tract, it is worthwhile to trace the metabolic fate of food. But first, agree on the terms. By the digestive tract we mean the stomach, small intestine and large intestine. Although "colon" is the wrong term. It is a large version of the small intestine no more than a snake is an enlarged version of the earth worm.

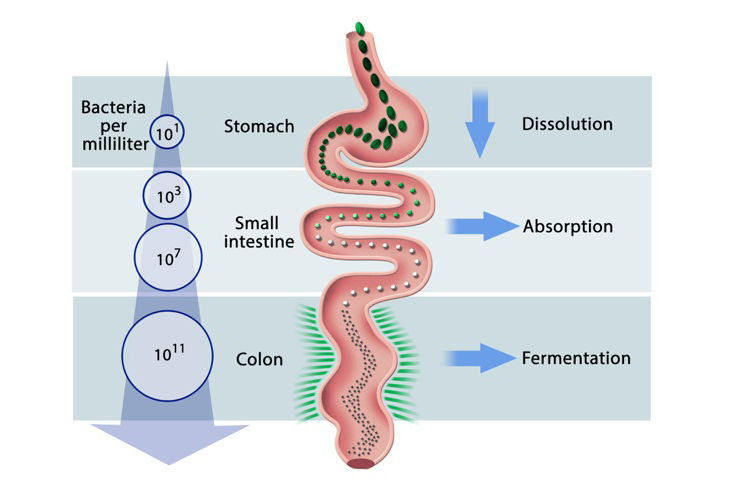

It would be better to call the stomach a solvent, the small intestine - an absorber, and the thick one - a transducer. These separate functions help explain why microbial communities in the stomach, small and large intestines differ from each other no less than the forest from the river. Environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity and sunlight affect the differences in animal and plant communities observed by tourists on mountain tops and in valleys. This is how microbiomes change throughout the digestive tract.

Imagine that you went on a picnic, and grill ribs on the grill. You come to the grill to assess progress. Pork ribs look great, so you pick up a couple and add a small pile of sauerkraut to them. Take yourself a bunch of corn chips and some celery. Get to the heap a beautiful looking skewer with vegetables. And of course you shouldn’t forget about pasta salad and pie.

You bring the ribs to your mouth and start to gnaw at them. The cabbage goes well with meat, and you add some cabbage to your mouth. Pasta is easily chewed, but you have to try over the celery. All this slips into the hatch and lands in the acid tank of your stomach, where the acid begins to dissolve the pieces of food. On a pH scale where 7 is a neutral state, and the smaller the number, the more acidic the environment, the stomach is quite impressive. Its acidity ranges from 1 to 3. For example, the acidity of lemon juice and white vinegar is about 2.

After the acid in the stomach has worked on the food, the resulting liquid mixture enters the upper part of the small intestine. The liver secretes bile, which immediately begins to work on fats, breaking them down into components. Pancreatic juices are attached to the digestive party. Your food is on the way to complete decomposition into the simplest molecules - simple and complex carbohydrates (sugars), fats and proteins. On average, there is an inverse relationship between the size and complexity of these molecules and their fate in the digestive tract. Small molecules, usually simple (fast) carbohydrates taken from refined carbohydrates in pasta, cake and chips, are absorbed relatively quickly. More complex and larger molecules are digested longer, so they are absorbed in the lower parts of the small intestine.

Three parts of the digestive tract and the number of bacteria per milliliter

Three parts of the digestive tract and the number of bacteria per milliliterLoops of the small intestine provide a completely different microbiome living conditions than the stomach. Acidity drops rapidly, and thanks to nutrients the number of bacteria increases dramatically, and they become 10,000 times more than in the stomach. But the environment for bacteria there is still not ideal. It looks like a rich river. And this is natural if we consider that about seven liters of fluids pass through it every day, including saliva, gastric and pancreatic juice, bile and intestinal mucus. And this does not take into account even a couple liters of other liquids that you use per day. The flow of liquids carries along food molecules and bacteria and carries them downstream. Because of the constant movement there is nothing delayed, and the bacteria have no chance to gain a foothold and participate in digestion.

On the way to the middle and lower parts of your small intestine, the fats, proteins, and some carbohydrates of your nutrient solution are already split enough to be absorbed and passed into the bloodstream through the intestinal walls. Pay attention - we said, "some carbohydrates." A lot of carbohydrates do not split at all. The fate of these complex carbohydrates, which your doctor calls fiber, is very different from simple ones.

Undigested, they fall into the viscous environment of the colon. The pH of this medium is neutral, of the order of 7, and there are developed paradise conditions for all sorts of bacteria, compared with the acid tank of the stomach or fast flows in the small intestine, with a low pH.

In the holy of holies of our entrails, the safe communities of microbes-alchemists use our large intestine as a transforming cauldron in which complex carbohydrates rich in dietary fiber wander. But this requires certain microbes. For example, the Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron create more than 260 enzymes that break down complex carbohydrates. Compared to them, the human genome looks pathetic - we are able to produce about 20 enzymes to break down complex carbohydrates.

Grain disaster

Our built-in boiler and the fermenters that manage it are similar to personal pharmacists. They can produce a huge amount of substances vital to our health and the normal functioning of intestinal cells. But we will benefit from butyrates (

butyric acid salts) and other alchemical products of the work of our microbiome only if we pour a large amount of fiber into the hatch.

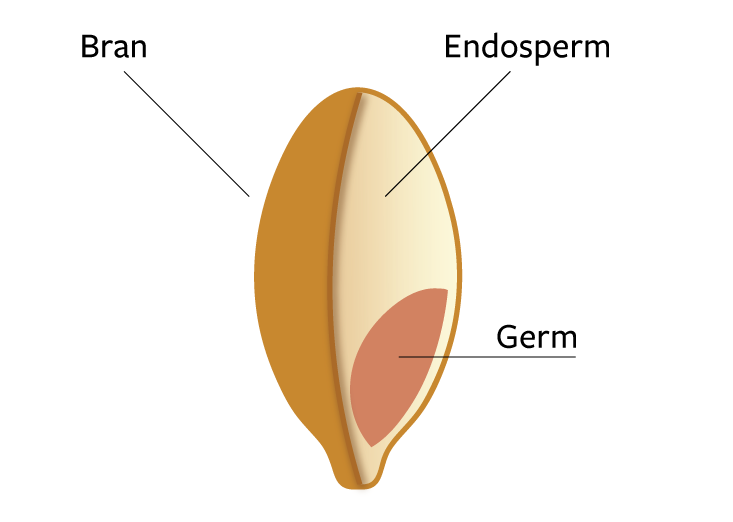

Arguing about such connections within the body, it would be nice to start with the seeds of the most popular cereals in the world, since they constitute the lion’s share of food consumed by people. Fortunately, cereals contain an almost perfect set of nutrients. Wheat, barley, rice - all of them have essential substances, proteins, fats and carbohydrates, as well as useful vitamins, minerals and other nutrients. But how can a large part of food consumed by humanity undermine our health?

It's all about the structure of the seeds of plants and what we do with them after harvest. Consider a grain of wheat. The outer shell, or seed coat, and the inner germ are small compared to the total weight of the grain. The seed coat is responsible for 14% of the total mass, the germ - for 3%. Despite their low weight, these parts of the grain are packed with nutrients. The seed coat is especially rich in complex carbohydrates, although chemists call them

polysaccharides - long chains of sugar molecules.

The remaining 83% of the grain weight is the endosperm. It contains most of the simple carbohydrates and almost all proteins. The endosperm is essentially the placenta of a plant. If the grain falls into the ground and germinates, then the endosperm, rich in simple carbohydrates, gives the grain nutrients until it grows roots and leaves and can feed on its own. And although germinating plants obviously need such a charge of energy, in large quantities it is not useful to us.

When we speak of refined grains, we mean that the seed coat and the germ are removed during grinding. Only the endosperm remains. If you grind the endosperm of wheat, you get white flour - it is easily digestible sugar for your small intestine.

Recycle all cereal seeds. This is the foundation of all that amazing variety of foods in grocery stores around the world, especially in Western countries. Refine corn, add fat, sprinkle with salt - and you get corn chips. Do the same with wheat and get crackers or bread.

Part of the cereals are treated because the fats are rotting - and what is made of refined flour is stored longer. Also, bakers do not like bran in flour, they violate the elasticity of the dough and prevent its rise. Removing these annoying impurities solves the problem. But it causes a lot of problems to our bodies. When a grain goes through grinding and processing, its ideal set of nutrients falls apart.

Looking back at the consumption of carbohydrates over the past hundred years, interesting trends can be identified. Americans in 1997 eat about the same amount of carbohydrates as in 1909 - just not the same. During this time, the carbohydrate content of raw grains in the diet has dropped from more than half to about a third. They were replaced by food made from processed grains. In other words, for the first time in the entire history of mankind, we mainly eat a part of grain with simple sugars (endosperm), and consume very few parts of grain with complex carbohydrates (germ and seed coat).

The small and large intestine digest the unprocessed grain in a completely different way than the processed one. When complex carbohydrates remain bound together with other molecules in the unprocessed grain, the enzymes need more time to search for carbohydrates and break them down. It's like trying to open a cardboard box wrapped in three layers with adhesive tape, instead of a box with a convenient flap for opening. Also, sugar molecules from unprocessed grains have to fight for space with protein and fat molecules in order to come into contact with absorbing cells of the small intestine, which also delays the process of sugar absorption. In general, if the grain remains intact, your body absorbs sugar much more slowly. And the non-digested part of the grains (and other food of plant origin) enters the large intestine, where it is enjoyed by fermenters who produce a huge amount of butyrates.

The processed grain secretes mountains of glucose, which our small intestine meekly absorbs and sends to the bloodstream. This causes the pancreas to produce insulin to transfer glucose from the blood to the cells. But using cells as a storage for sugar can lead to other problems. And our surprisingly effective body is trying to solve the problem, turning excess sugar into fat and redirecting the excess to the storage, fat cells. When we need this energy, for example, at night, when breakfast is still far away, it will be available for use. But the abundance of processed carbohydrates, turning into fat, exceeds the needs of the average American. This is a recipe for inflammation, a path to type 2 diabetes, obesity and other problems.

The amount of meat in the western diet can also lead to problems. If there is a lot of it, animal protein does not break down completely, reaching the end of the small intestine. In this case, the partially digested protein will enter the colon. And when the colon bacterium is found with partially digested protein, another alchemy begins - the decay of proteins.

The problem with decay occurs due to the composition of animal protein - there is a lot of nitrogen and a little sulfur in it. Ammonia,

nitrosamines ,

hydrogen sulfide - these concepts say little to the average person. But bacteria create them in the process of decay. And these compounds are toxic to the cells lining the colon. They interfere with the absorption of butyrates, which deprives the cells of the colon of the energy they need to work. The space between the cells begins to increase, the intestinal contents begin to leak into the surrounding tissues and a

syndrome of increased intestinal permeability occurs [the presence of the syndrome

is not recognized by all medical scientists - approx. trans.]. Cells that are undernourished stop working normally, and waste begins to accumulate in the cells, which prevents them from performing other functions. In addition, the

goblet cells , whose main task is to secrete mucus that envelops and protects the intestines, produce it more slowly. The intestinal walls become more susceptible to pathogens and physical damage. And this is not a joke: the large intestine is an active place, the cells lining it constantly regenerate. If they are not replaced regularly, the effect is the same as that of an unrepaired house. Many small problems lead to the emergence of large, and the house begins to fall apart.

Other problematic by-products appear in the colon. High fat content in food stimulates the liver to produce bile. We need bile, it works as a detergent that breaks down fats into smaller molecules that are digestible. Almost all the bile used in the small intestine, after the breakdown of fat is transferred back to the liver. But the key word is almost. 5% of bile moves along the digestive tract and is in the large intestine. If a person eats more fat, more bile is secreted, and more bile enters the large intestine as a result.

And, of course, this bile accepts and converts the microbiome. They turn it into very bad compounds,

secondary bile acids . They, like rotting products, are toxic to colon cells.

Omnivore inside us

As the paleodietists like to remind us, people have been eating meat for a long time. They point out that meat is an excellent source of nutrients, especially if the animal eaten grew without antibiotics and fed naturally. Vegetarians and vegans warn us, indicating that people on a vegetable diet usually suffer less from cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes. They also indicate that plants, unlike animals, have a terrific set of substances that prevent cancer.

In other words, both of these dietary perspectives contain the seeds of truth. Consider another option - the combination of both diets makes sense, given the way our microbiome will do with meat, fat and plants.

This is how things can happen. Imagine that the byproducts of decay of undigested meat and secondary bile acids saturate the colon cells. DNA mutations occur, and several abnormal cells begin uncontrolled regeneration, ignoring instructions from self-destructing cells of the immune system. But irrigate this scene with a tsunami of butyrates, and intestinal cells perk up. Traitor cells are amenable to immunity cells. Huge quantities of undigested complex carbohydrates derived from plant foods enter the colon, clean it of secondary bile acids, reducing the interaction of these carcinogens with intestinal cells. Normal growth and cell function are restored, they support the health of the “cauldron” and the whole body as a whole.

This scenario is ideal in terms of both health and ecology. Fiber-processing bacteria have solutions to the problems caused by bacteria that break down proteins. Plus, all the inhabitants of the boiler are fed - either complex carbohydrates, or the remnants of undigested protein and bile acids. As long as the activity of cellulose fermenters predominates in the large intestine, it works as a first-aid kit and not a toxic waste dump.

We are the most omnivorous creatures on the planet, we have access to a huge variety of domesticated grains, animals and wild plants. There is little that people do not eat: from

whale oil , pig intestines, caterpillars, rotten fish, raw fish and algae, to meat, dairy products, bread, fruits, nuts and vegetables. But many diets and gurus diets avoid our omnivorous. They constantly offer to eat a small (and constantly changing) set of products. Ideas about what we need to eat, rush from one extreme to another like a pendulum — some more meat, some more vegetables, some less fat, some more certain fat, some uncooked cereals, now no cereals.

It is not surprising that many people are sick of such diets, or tired of them, or all at the same time. To get some advantages, you need to care about what exactly we are feeding our personal alchemists. The mechanics are pretty simple. Choose a medium-sized plate and let the main ingredients of your meal be vegetables, legumes, greens, fruits and unmilled grains. Add meat and some healthy fats if you wish. Desserts and sweets are a special food, so save it for special occasions.

Of course, this style of food is badly “sold”. He disposes of the assessment of food from the microbiome point of view, does not limit the list of food, does not call for counting calories and “go on a diet”. This advice does not look unexpected and does not destroy any basis.

Naturally, people with special intestinal problems or allergies to certain foods should have a special approach to diet. But for most of us, the key to healthy eating is just balance and variety, plus eliminating refined carbohydrates. In other words, more grass for your fiber fermenters, so that they release more nutrients than your bacteria produce by-products, which contribute to protein rot and bile processing. Consuming fiber in large quantities means feeding your boiler with fermentation fuel, thanks to which things that are useful to you will appear in it.

If by this time you have not yet developed respect for your intestines and its capabilities, try to present it differently. The gut of each of us is like a garden. As gardeners know, plants in a garden will live well and resist pests and parasites only if they grow on good soil. The key to a vibrant and healthy garden - inside and outside our bodies - in the cultivation of legions of beneficial bacteria. The unclassified ingredient for this is

mulch . Exactly, plant material is just as important for the tiny alchemists of our intestinal cauldron as it is for garden soil. Feeding them with such food, we reap the first-aid kit with a good assortment.