As leaders, they lose their mental capacity - first and foremost, the ability to see people through - which are necessary for them to come to power.

If the authority was prescribed as a prescription drug, it would have a long list of side effects. She is toxic, she spoils, she can even make

Henry Kissinger consider himself sexually attractive. But can it cause brain damage?

When various lawmakers last fall attacked John Stumpf at

a congressional hearing , it seemed that each of them found a new way to criticize the former CEO of Wells Fargo for

failing to stop nearly 5,000 of his employees from setting up fake accounts for customers. But the most interesting was the behavior of Stumpf. This was a man who had risen to the heights of the most valuable bank in the world at that time, while he seemed completely unable to perceive the mood of those present. Although he apologized, he did not look like a man of humble and complete repentance. But he did not seem defiant, complacent or hypocritical. He looked disoriented, like a cosmic tourist from the planet Stampf, who was experiencing the effects of jet lag, in which respect for him is considered a law of nature, and 5000 is a fairly small number of people. Even the most direct taunts: "

Yes, you probably joke " and "

I can not believe what I hear, " could not stir it.

What was going on in Stumpf's head? A new study suggests that it is better to ask - what did not occur in his head?

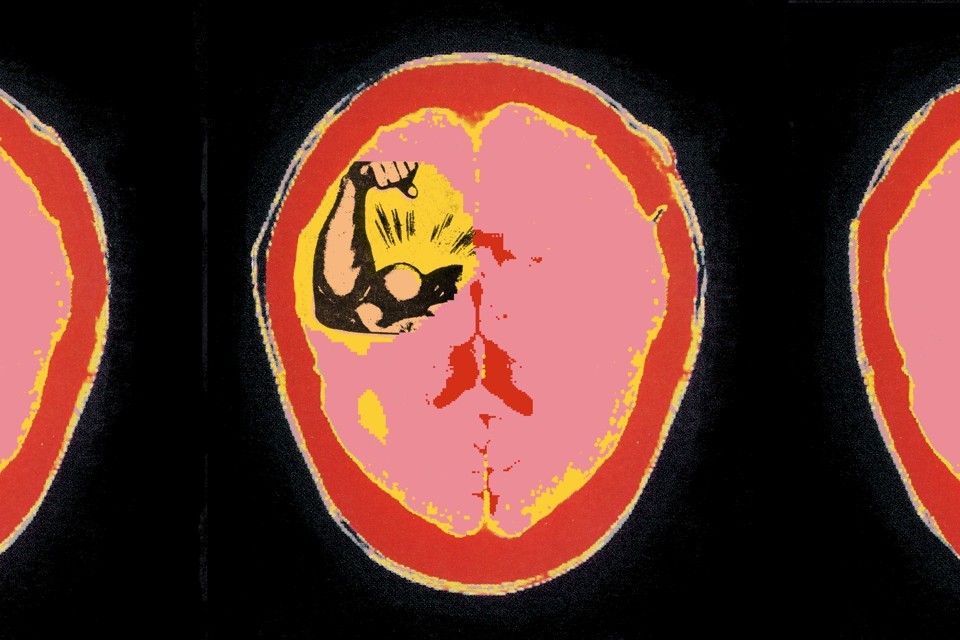

Historian Henry Adams spoke metaphorically, and not in medical terms, when he described power as "a kind of tumor that kills the sympathies of the victim." But this is not so far from the facts disclosed by Decher Keltner, a professor of psychology at the University of California at Berkeley, after many years of laboratory and field experiments. The subjects, endowed with power, as he discovered in two decades of research, behave as if their brains are injured - they become more impulsive, less aware of the risks, and, most importantly, they are worse at evaluating events from the point of view of other people.

Suhvinder Obhi, a neuroscientist at McMaster University in Ontario, recently described something similar. Unlike Keltner, who studies behavior, Obha studies the brain. And when he studied the heads of people endowed with power, as well as people who were not clothed with a

transcranial magnetic stimulation apparatus, he found that power weakens a certain nervous process, “mirroring,” possibly the cornerstone of empathy. This gives a neurobiological basis for what Keltner called the "

paradox of power ": when we receive power, we lose some of the opportunities that we needed to obtain it.

The loss of this opportunity was demonstrated by various creative methods. In 2006, in the

study, subjects were asked to draw the letter “E” on their foreheads so that others could read it — in order to perform such a task, it is necessary to imagine how a person sees you from his point of view. People who believed they had power were three times more likely to make mistakes by drawing the letter “E” so that it was directed correctly for themselves, and incorrectly for everyone else (George Bush is remembered, holding the US flag backwards) at the 2008 Olympics ). Other experiments have shown that people with authority define the feelings of other people in a photograph worse, or guess how their colleague can interpret a remark.

The fact that people tend to repeat the expressions and body language of their superiors can aggravate this problem — subordinates do not give reliable signs to superiors. But more importantly, according to Keltner, is that influential people stop repeating after others. Laughing with others or straining with them is not just trying to get into trust. These actions help to evoke the feelings experienced by other people, and allow you to look into the soul of people experiencing them. People in power "stop simulating someone else's experience," says Keltner, which leads to what he calls a "lack of empathy."

Mirroring is a more subtle version of mimicry, completely happening in the head without our participation. When we look at how someone performs an action, the part of the brain that we would use to perform the same action is activated as part of the sympathetic response. This is best understood by the example of the substitute experience. This activation was

attempted to achieve Obha with his team, by letting the subjects see a video on which a hand squeezed a rubber ball.

For subjects who did not have access to power, mirroring worked normally: the nerve paths that they would use when compressing a real ball were clearly activated. And a group of people endowed with power, such a clear activation was not.

Did they have a broken mirror response? Rather, muffled. None of the participants actually had permanent power. These were college students who stood out to recall the situations in which they were in charge. Muting is likely to disappear after the corresponding sensations disappear - the structure of their brain was not damaged after a day spent in the laboratory. But if the effect lasted longer — say, if Wall Street analysts whispered their greatness quarter by quarter, board members offered them additional incentives, and Forbes magazine

would praise them — they could endure what is known in medicine, as "functional" changes in the brain.

It became interesting to me - is it possible that the powerful of this world simply cease to put themselves in the shoes of others, without losing this ability. It turned out that Obhi conducted another

study that could help in finding the answer to this question. This time, the subjects were told what mirroring was and asked them to consciously increase or decrease their response. “As a result,” they wrote with the co-author, Catherine Nash, “there was no difference.” Desire didn't help.

Sad discovery. Knowledge must be power. But what good is that you know that power robs you of knowledge?

The best conclusion that can be made from this is that changes are not always harmful. The study claims that power gives the brain the opportunity to ignore peripheral information. In most cases, this gives an increase in efficiency. But a side effect is the blunting of social opportunities. But this is not necessarily bad for people in power or groups of people led by them. As Susan Fisk, a psychology professor at Princeton,

convincingly proves , power reduces the need to read the nuances of human behavior, because it gives us the resources we used to beg for from others. But in a modern organization, the maintenance of such power is based on a certain level of organizational support. And the number of examples of the arrogance of those in power who abound in headlines suggests that many leaders cross the line separating them from counterproductive whims.

Since they no longer appreciate the characteristics of other people as well, they are beginning to rely more heavily on stereotypes. And the less they see, the more they rely on a personal “world view”. John Stumpf saw Wells Fargo in front of him, where each client had eight accounts (and often noticed the staff that “eight” rhymes with “greatness" [eight - great]. "Cross-selling," he told Congress, is a deepening relationship ".

Surely nothing can be done about it?

Yes and no. It is very difficult to prevent the authorities from influencing their brain. Sometimes it's easier to stop feeling in power.

Our way of thinking is not influenced by the position or position, Keltner reminds me, but the state of thoughts. Remember the times when you didn’t feel that you had the power and your brain could reconnect with reality, research suggests.

Some people are helped by memories of experiences in which they did not have power — and bright enough memories can provide some kind of permanent protection.

An amazing study , published in The Journal of Finance, says that CEOs who survived a natural disaster with a large number of victims in childhood love to risk much less than those who have no such experience. The only problem is, according to Raghavendra Rau, a co-author of the study and a professor at the University of Cambridge, that directors who survived the cataclysms without a significant number of victims also like to take risks.

But arrogance helps to contain not only tornadoes, volcanoes and tsunamis. PepsiCo CEO and Chairman Indra Nooyi sometimes tells the

story of the day she learned about her appointment to the company in 2001. She came home, bathed in a sense of her own grandeur and importance, and her mother, before she had time to share the news, asked her to drive for milk. In a rage, Nuyi came out and bought milk. “Leave this damn crown in the garage,” her mother told her when she returned.

The moral of the story is that Nuyi herself tells it. It serves as a useful reminder of ordinary duties and the need to remain mundane. Nooyi’s mother in history plays the role of a “toe-holder” - this term was once used by political advisor Louis Howie to describe his relationship with President Franklin Roosevelt, whom Howie always called Franklin.

For Winston Churchill, this role was played by his wife Clementine, who had the courage

to write : “My dear Winston. I must confess that I notice the deterioration of your manners. You are not as kind as you once were. ” She wrote this letter that day when Hitler entered Paris, then tore up, but then sent it anyway. It was not a complaint, but a warning: she wrote that someone confessed to her that Churchill behaved with his subordinates at meetings “so arrogantly” that “he did not accept any ideas, either good or bad” - and this was due with the danger that he "will not achieve the best results."

Lord David Owen - a British neuroscientist who became a parliamentarian who served as foreign minister before becoming a baron - recalls Howie’s story and Clementine Churchill in his 2008 book, In Disease and Power, an exploration of various disorders that affected efficiency British Prime Ministers and American Presidents since 1900. Some suffered from stroke (Woodrow Wilson), alcohol abuse (Anthony Eden), or possible

bipolar disorder (Lyndon Johnson, Theodore Roosevelt), and at least four more suffered from a disorder that is not considered as such in the medical profession - although Owen argued that they should recognize him.

“Syndrome of arrogance,” he and his co-author Jonathan Davidnos wrote in an

article in 2009 in the journal Brain, “is a disorder associated with the possession of power, especially power associated with the exorbitant success held for years and with minimal restrictions imposed on leader. " Its 14 clinical properties include: contempt for others, loss of contact with reality, restless and thoughtless actions, demonstration of incompetence. In May, the Royal Medical Society held a conference jointly with

the Daedalus Foundation , an organization founded by Owen to study and prevent arrogance.

I asked Owen, who admitted to himself the most healthy predisposition to arrogance, whether something helped him not to break away from reality, anything that people with real power could emulate. He shared some strategies: memories of episodes destroying arrogance, watching documentaries about ordinary people, the habit of reading voters' letters.

But I believe that the best test of Owen’s arrogance may be his recent research. He complained that commercial enterprises had no interest in arrogance research. The situation with business schools is no better. The presence of disappointment in his voice spoke of a certain amount of helplessness. But no matter how useful it is for Owen, it follows from this that the illness, often observed at meetings of the board of directors and in the offices of the authorities, will not soon receive his medicine.