What do 50 Nobel laureates think about the problems of science, universities, the world - from populist politics and mobility of researchers to artificial intelligence and threats to humanity

I think that practically none of the problems I see today would bother me if we knew how to work together and carefully think about problems together in a rational way, connecting fears and needs with a rational understanding of the world.

So said Nobel laureate

Saul Perlmutter at the World Academic Summit of Times Higher Education (THE), held at the University of California at Berkeley in September 2016.

However, a professor of physics from Berkeley does not believe that today's methods of teaching and financing science contribute to the best disclosure of all possibilities for solving problems, because researchers are not given enough freedom. “You cannot order a technological breakthrough. “You need to let people try different ideas,” he said. “When you send very smart people to solve existing problems, they invent all sorts of things.”

Regarding the study of the expansion of the Universe, which led him to receive the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011, Perlmutter thinks that today no one would have financed this kind of research. "It would be very difficult to justify in a world in which you count every penny and take care not to spend money."

Such statements of the Nobel laureate, of course, caused a lively discussion. But do they agree with this approach to the problems faced by the world, science and scientific institutions, other members of this elite club? In order to find out, THE magazine united with the organizers of the meetings of the Nobel laureates in Lindau, and conducted among them polls on these issues.

Since the first award in 1901 in the field of science, medicine or economics, less than 700 people have received it. Of these, 235 are still alive. With the help of the German organizers of the annual conference, THE was able to interview 50 of them.

The article presents sometimes unexpected views of one of the most intelligent and illustrious minds for everything, from the merits of the existing system of financing to the greatest threats to humanity.

Financing

More than a hundred years, the Nobel Prize was the greatest reward in science. And although a small number of individuals received an award when they were not yet forty, most of the winners were awarded at a more respectable age for the research that had been going on for decades, often followed by large teams and sponsors millions.

But with increasing competition in the fight for grants and with increasing pressure exerted on scientists by politicians and financiers, due to the fact that the latter expect from the first predictable results that can really influence the world, do the scientists we interviewed agree with that Really, the studies for which the nobel prizes were often awarded were no longer popular? Specifically, do they believe that their own rewarded research could be carried out in today's financing conditions?

In general, all expressed quite optimistic. 37% said that they would definitely be able to conduct their research in the current funding system, and 47% said it was “possible.”

“First of all, the quality and originality of research is still taken into account,” said one laureate from Switzerland, and another scientist from the United States noted that “society was and continues to be very generous” in the matter of research. Another optimistic respondent, living in Germany, says that he would be sure that he would receive a grant from the European Research Council to run long-term projects.

Several prize winners criticize the growing bureaucratic obstacles around research and the emergence of a trend toward preferential funding for applied science, but they remain confident that they would succeed in the current situation. “I believe that my hard work and inspiration would overcome the limitations on getting funding,” says one Florida scientist.

"Even in the most research-oriented environment, you can find a place for fundamental research," adds the laureate from New York.

Many respondents believe that their premium was weakly related to the problem of research funding, since these studies were either inexpensive or funded from their own pocket. “I always worked cheaply,” says one laureate from Britain. “I was a student, and I did not need funding,” adds another.

Do you think that you could make a discovery deserving of a premium in today's financing situation?

0% - definitely not

16% - probably not

47% - probably yes

37% - definitely yes

However, 16% of laureates believe that they probably would not have been able to conduct their research in the modern world. Richard Roberts, an English biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1993 for his work in the field of gene

splicing , doubts that his breakthrough would have been possible in the current situation.

Roberts defended his doctoral degree at Sheffield University, and then moved to Harvard, and then to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island. And the time spent in the last institute, which was then led by DNA pioneer James Watson, was crucial for his breakthrough.

“If I were in the usual academic position, I don’t think I would receive funding for my proposal,” says Roberts, who now works for the private research company Biolabs in New England. “The subject of my request was a simple question, to which, as it was believed, the answer was known - but in fact it turned out to be wrong,” he adds.

Roberts is worried that scientists lose "an incredible amount of time" to write giant sentences, most of which fail. And those who receive funding need more flexibility and time to chase for discoveries, which at first glance seem to be unsuccessful.

“Good scientists know how to write a grant application, but as a result you are researching what is not included in this grant,” he explains. “When experiments fail, you need to know why you screwed up, or nature tries to tell you something.”

Peter Agra , an American molecular biologist who received the 2003 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, agrees that the high difficulties in obtaining grants can deter many people from trying to make a research career.

“No one would have done this work and would have worked so hard as they did, knowing that the chances of receiving a grant do not exceed 5%,” says Agra, now director of the Malaria Institute. Johns Hopkins at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at the University of Baltimore.

But, nevertheless, the competitive level between researchers and a certain level of risk is normal, adds Agra. “Science is not a French social sphere, you do not need to embed full insurance in it,” he says.

Other laureates agree with the assessment of the current climate of financing from Roberts. “Today there is a shortage of long-term positions and long-term financing of risky projects that could lead to a Nobel Prize,” explains one of the laureates from Germany. He was echoed by a New Jersey laureate, saying that "reducing support for core research means reducing the desire to finance risky projects."

“

Brexit only adds uncertainty to the future climate of financing,” adds the winner from Britain.

One of the award winning projects from the United States was "a side, not my main project." But this winner is worried that such side projects in the modern world are not encouraged. “The modern assessment of research is too short-sighted, and makes young people engage in fashion trends. It hampers the healthy growth of the scientific community. ”

International mobility

John mater

John materOver the past year, internationalism has markedly passed. The growth of anti-immigration populism on both sides of the Atlantic threatens to harm international mobility of scientists - if not specifically, then as a side effect.

At the same time, at least one Western leader still welcomes foreign scientists. In June, French President Emmanuel Macron invited US scientists looking for a new home, based on the announcement by Donald Trump that the US is leaving the Paris climate agreement. Macron called "all scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, responsible citizens, disappointed with the decision of the US President to come to us and work with us."

But will such initiatives, which fall in the high-profile headlines, lead to significant scientific breakthroughs? Is the international mobility of researchers important for expanding the boundaries of knowledge?

Nobel laureates emotionally insist that this is the case. 43% of them noted international mobility as “very important” for research, and 38% called it “critical”. Every fifth person says that it is “quite important”, and no one considers it completely unimportant.

Often there are phrases “there are no boundaries in science” and “research is a joint and global action”. “No one can tell where great ideas will appear or who they will have,” explains John Mather, chief cosmologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, whose work with satellites brought him some of the Nobel science in physics in 2006. "But we know that people are moving to those organizations that they consider promising and which support their research."

Another US laureate adds that “most progress in advanced research is conducted by a very small number of people. In this sense, it is important to have a larger sample. ”

After assembling talented world-class scientists into a single research team, paradigm shifts often occur that take science to a new level, Peter Agra explains.

“Science is a bit like the movie business,” says Agra. “Often the status of the industry really promotes the release of the blockbuster.”

How important is international mobility for research?

0% - not at all important

0% - not very important

19% - pretty important

43% - very important

38% - is critical

But a laureate from Chicago said that international mobility is also important for students: "Our best students come from abroad."

One California laureate suggests that the advent of Skype, FaceTime and other video conferencing technologies means that traveling abroad has ceased to be as important as the previous generation of researchers. However, many respondents believe that newsgroups are a bad substitute for face-to-face meetings.

“Only by exchanging ideas with the greatest minds and institutions around the world — and this is best done through the personal relationships of researchers, even in the digital age — can we hope to make the earliest progress in advancing knowledge,” says Brian Schmidt, an astrophysicist who taught the 2011 award Physics, together with Perlmutter and Adam Riesz from the University. Johns Hopkins, now serving as vice head of the Australian National University.

But the Japanese laureate notes that "researchers are often inspired by familiarity with other cultures." Therefore, "international cooperation helps the joint creation of new scientific knowledge." The laureate from the USA supports him: “Ideas come from everywhere, but often different learning and research styles adopted in different countries and institutions lead to the emergence of different points of view — namely, this combination is needed to successfully solve complex problems.”

For one laureate, international mobility is a personal whim. “For the past 15 years I have lived in South Africa, Britain, Israel and the USA. I can not stay in one place for more than a few weeks - explains the researcher. “Not sure if this is good, but it’s so great."

Populism and political polarization

Donald Trump dismissed climate change as a “fraud”, and this is often considered one of the symptoms of the “post-truth” era, where science and facts can be dismissed in favor of baseless and fanatical views. Remarque former Minister of Education of Britain Michael Gove during the Brekzit campaign on the fact that the British have enough experts (in this case economic experts were meant), made many alarm calls at British universities ring.

Does the spread of populism and political polarization threaten modern science? Nobel laureates believe that yes. 40% believe that these phenomena pose a deadly threat to scientific progress, and 30% call them "a serious threat." Only 5% (two respondents) do not care at all about this, and 25% consider them to be a “moderate threat”.

“Today, the facts are questioned by people who prefer to believe in rumors, rather than proven scientific facts,” said Jean-Pierre Savage, who won the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. “Education is the only answer to that.”

But one laureate from the United States noted that “it’s terrible when people start believing in false things, and even worse when governments encourage them to believe in facts that are obviously false, and ignore evidence that is scientifically proven and evidence-based.”

Another laureate notes that "any measures that suppress the exchange of ideas are detrimental to science," and the Japanese laureate urges the scientific community to "unite around the world against all unacceptable movements that deny a certain and natural truth."

How serious are the threats to scientific progress of populism and political polarization around the world?

5% - are not threats

25% - medium threatening

30% - seriously threatened

40% - mortally threatened

Several laureates criticize the “intellectual arrogance” of some political leaders, although only one of them directly calls Trump. However, describing climate change concerns as a special demonstration of ignorance and delusion is “a very bad strategy,” according to Mather from NASA.

“The results on climate change are clear; Much less clarity on what to do with them, he says. “People are beginning to understand that simply complaining about other people is pointless.” He believes that it would be more productive to insist on increasing investments in energy-saving technologies.

Several laureates do not believe that populism is a threat to scientific progress, but they are concerned about where it can lead. One researcher from New York explains that "populism is not dangerous to science until it turns into nationalism."

One laureate from the United States believes that not so much populism as demagoguery, that is, “turning to people's fears,” as a result “will lead to a decrease in research funding in favor of tax cuts or more 'pressing' problems. The real danger will be to turn this into anti-intellectualism. ”

Some respondents are more optimistic.

“Despite the rather large and shrilling minority, it seems to me that during my life the world began to more understand the role of science and technology in improving human well-being,” one of them notes. “The bias remains positive.”

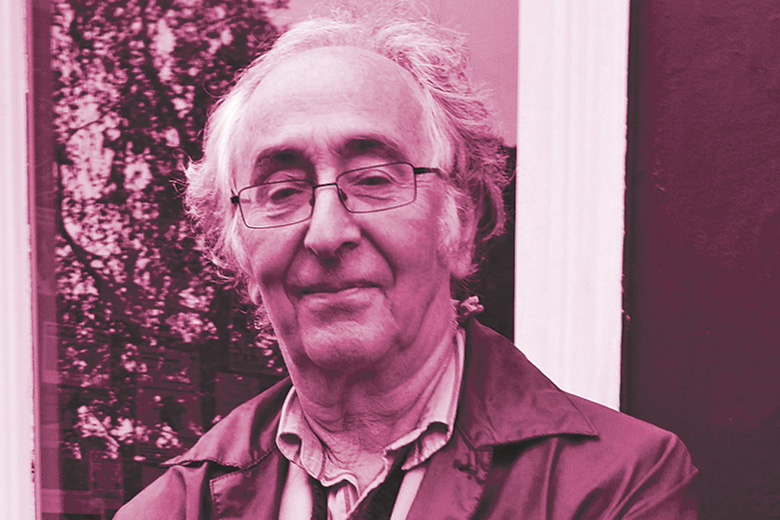

Brian josephson

Brian josephsonResponding to questions about the most difficult problems of universities, our laureates constantly returned to the same topic: money. Two out of five mentioned among the problems either the availability of education at current prices, or the underfunding of universities.

“The cost of tuition at private universities in the US is breaking records, and the support of public universities in many states is fading,” explained one respondent. The second talked about "growing inequality between public universities and wealthy, tax-exempt institutions."

Another laureate from the United States explains that “it is increasingly necessary for students to have very rich parents. In the best private universities, the number of students whose parents are in the first percent of the income scale is equal to the number of students with parents in the bottom 50% of the income scale. ”

What are the biggest problems for universities in your country and around the world? (it was possible to choose several options)

42% - lack of money

13% - lack of academic freedom

11% - populism and post-truth

8% - restriction of international student exchange

8% - lack of access to capable students, regardless of their biography

8% - bureaucracy

3% - instrumentalism

3% - excessive expansion

3% - snobbery

3% - students and teachers do not reach the standards

Roberts believes that "the biggest problem of universities is that politicians do not listen to science and education." He mentions "excessive bureaucracy trying to measure the returns of science." “Why do bureaucrats consider this a good idea, and why do we let them do it?” He asks.

Other respondents complain about the growing power of administrators, and one laureate from Southeast Asia says that "the government is trying to more and more control the behavior of scientists, which makes their lives less attractive and repels long-term projects."

Universities need to be “more open to such heretics like me — then science progress will accelerate,” says Brian Josephson, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1973 at the age of 33. His subsequent research in the field of parapsychology, conducted at Cambridge University, caused a wave of criticism.

Several respondents also complain about the suppression of free speech at universities. One California laureate condemns "suppressing the free exchange of views by people who rebel when an alternative opinion emerges."

Artificial Intelligence

Recently, the press has been full of articles announcing the advent of the era of artificial intelligence and expressing concerns about what this means for the workers. If computers are already playing chess better than people, will not machines and researchers be replaced? Will the day come when the robot (or its programmer) will receive a Nobel Prize?

No, according to our interviewees. On the question of whether AI and robots would reduce the need for humans, researchers, almost three-quarters answered either "hardly" (50%) or "definitely not" (24%). And only 24% said it was “possible.” Definitely only one voted for this.

“The AI showed little in terms of creativity and the ability to ask new questions,” says one California laureate. The French laureate adds: "Only human intellect and his thoughts lead to the emergence of new and original concepts." The laureate from the United States believes that "robots have no imagination or foresight."

“Do you think that if you put together a million robots, they will give out something like Mozart’s operas Don Juan or Everybody Do That, or Schubert’s The Beautiful Miller's Works or Winter Route?” Asks the laureate, who adores classical music.

Will the need for AI humans and robots decrease?

24% - definitely not

50% - hardly

24% - possible

2% - definitely

However, many respondents believe that robots can play an important role in laboratory work. “Robots will be able to facilitate the monotonous work of trainees in the experimental field,” says one of the winners from the United States. Another respondent who works in the field of biomedicine, predicts that machines will be able to take on "mechanical functions, such as cloning, animal care and equipment maintenance," which will allow small groups of researchers to work more efficiently.

Some laureates predict that AI may generate demand for more researchers. “Each solved task opens up new ones, it doesn't matter if it was decided by a person or a robot,” says the German winner. A survey participant from the United States explains that increasing the number of human-machine partnerships will open so many new and fruitful research paths that "probably more people will be involved in them."

Australian National University Schmidt says that "probably AI and robots will complement the skills of researchers, not replace them." But he adds: “Of course, if we create an AI, we can let it do all the work, while we ourselves will rest on the beach at this time — or the flood of self-taught self-taught masters will flood us.”

The greatest threat to humanity

Two respondents consider such a threat to AI. However, much more Nobel laureates are concerned about the environment. Every third considers global warming and overpopulation a threat.

This number is especially surprising against the background of

the US withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement and the appointment of Donald Trump to the post of head of the US environmental protection agency skeptic for climate change, Scott Pruitt. And if Trump believes that climate change is China’s fraud to harm American industry, it’s clear that Nobel laureates disagree.

“Climate change and providing enough food and clean water to a growing population is a serious problem facing humanity,” says one of the American winners. “Science needs to address these tasks, as well as to educate the public in order to generate the political will necessary to accomplish these tasks.”

Roberts believes that providing food for a growing population is the greatest challenge facing humanity. He is concerned about the presence of large-scale resistance to the use of genetically modified animals and plants to solve this problem, despite the scientific consensus confirming their safety.

“Vulgar disregard for scientific opinion will lead to a worldwide crisis,” predicts Roberts, mentioning a June letter signed by 124 Nobel laureates, calling for Greenpeace and other non-governmental organizations to end their campaigns against certain types of biotechnologically improved grain crops.

“Telling people that they cannot eat or grow food that can prevent their hunger is disgusting,” says Roberts, adding that climate change will increase the need for GMOs more than ever.

What is the greatest threat to humanity? (it was possible to choose several options)

34% - population growth

23% - nuclear war

8% - infectious diseases and immunity of diseases to drugs

8% - selfishness, lies, loss of humanity

6% - ignorance, distortion of truth

6% - fundamentalism, terrorism

6% - Trump and other ignorant leaders

4% - AI

4% - inequality

2% - drugs

2% - Facebook

But Mater from NASA notes that “people are very busy with the greatest experiment on climate change since the ice age, but science has the potential to completely change the system of economic rewards that encourage the use of fossil fuels. In other words, if renewable energy becomes cheaper than fossil, people will switch to it very quickly. ”

Missile testing of North Korea exacerbates tensions on the US-China line, and problems with [

supposedly approx. trans. ] Russia's intervention in the elections in the United States, as well as its actions in Ukraine, in the Crimea and Syria, explain why nuclear war is the second most popular threat respondents referred to.

Among those who mentioned this problem, 23% of respondents also have a laureate from Israel who complains of "militaristic dictators". The laureate from Germany notes "populist regimes with nuclear weapons", and Mather is more worried about nuclear weapons that could fall into the hands of terrorists.

Among the other threats mentioned are medical concerns, such as a worldwide epidemic and resistance to antibiotics, fundamentalism and terrorism, the loss of altruism, honesty or "humanism in the process of our aspirations in the Internet era and its temptations." Two particularly noted Trump: “I think science can do little here,” one said.

Several laureates are optimistic that the apocalypse is unlikely to come.

“People are very successfully changing the world for the better,” says one. Another acknowledges that "humanity has several unlikely but existential threats, including an epidemic, nuclear war, and AI."

But the laureates believe that science can help with this: “The ideal insurance is to make humanity an interplanetary view. And science, obviously, has a big role in this. ”

Peter Agra about villain Trump, prime minister Beckham and excessive geekiness

Donald Trump often boasts a great electorate, but there are hardly many Nobel laureates in it, given our survey.

Many laureates treat with disdain the billionaire and property owner who occupies the White House, regarding him as a direct threat to scientific progress. But few people criticize him so much as Peter Agra, a malaria researcher at the University. Johns Hopkins in Batimore, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2003 for opening

water channels in cell membranes .

“Trump could have played the villain in the Batman movies — everything he does is either evil or selfish,” Agra told THE magazine, describing the US president as “extremely little-informed and evil.”Agra is particularly worried about how Trump “takes pride in his ignorance” to appeal to a group of Americans who are happy to dismiss the opinion of scientists.People who support the populist denial of the Trap on climate change under the pretext of “fraud,” or scientific opinion in general, “feel threatened by educated people,” Agra said. "We usually come from wealthy families, we have investments, beautiful houses, we read books - they do not respect this."Science has done enough to reduce this growing cultural divide between society and the scientific community, according to Agra. Many scientists abuse the way of a geek, a person not from the world of everything, from which most people easily deny.“When a person from a distance can recognize a scientist, it’s probably not the best of our possible images,” says Agra, and jokes that “maybe we shouldn’t look like Doc Braun from Back to the Future.” He is delighted with the "phenomenal work" carried out in scientific laboratories around the world, but believes that intelligence is not all that a great scientist needs. “I don’t think that I had an incredible scientific talent as a student — I was just as interested in journalism or politics,” he explains. “All the successes I have achieved are essentially a miracle.”After graduating from a chemist at Augsburg College in Minneapolis, Agra enrolled at John Hopkins Medical School, which freed him from conscription to the Vietnam War. And although the laboratory to which he ended up was “very good,” she lacked famous names. His supervisor, Vann Bennet, was his classmate at medical school. However, Agra was allowed to work in the direction he was interested in as a graduate student, and his work with cholera paved the way for a study that deserved the Nobel Prize.“If you just watch what is actively discussed in the scientific media, you can miss something,” says Agra, adding that, according to his experience, “fantastic science often comes from little-known places.”But any young scientist who dreams of a Nobel Prize should banish such thoughts, advises Agra. “If you have a graduate student trying to defend a doctoral and change the world at the same time, he is unlikely to succeed in both,” he says.And if Agra worries about the villains in world politics, he still hopes that equally heroic figures will stand up to fight them. However, his assumption about a new possible progressive politician in Britain seems unlikely. “I once met David Beckham in the waiting area of an airport in New Zealand. It was late, but he graciously agreed to write a note to one of my daughters, his fan - he was an excellent gentleman. ” "Perhaps a star candidate can do something good."