Emotions and intelligence, physics and lyrics. How long has the opposition of these categories lasted?

It would seem that everyone knows that emotions interfere with intellect and we value composure in people, admire their ability to resist emotions and act rationally. On the other hand, the lack of emotions is also not very to our liking. It is possible that not everyone likes pedants and crackers, and when they show emotions, it happens to us, it seems, that this is humanity itself.

What are emotions? Is this an exclusive quality of a person, or are animals also possessed by them? And finally, do robots need emotions and can they even have them?

Everyone who is interested in such issues and likes to philosophize, welcome under cat.

Introduction

This article is a continuation of an article published earlier under the title

The evolution of intelligence: the beginning . It sets forth a rather simple idea that if we assume that intelligence did not appear at once, but has gone the evolutionary path from extremely simple forms to its modern model of the last generation (human intelligence), then the traditional definition of intelligence , sharpened by a person, will obviously require a revision to side of greater versatility. In addition, in the article, for the convenience of reasoning, a classification of evolutionary levels of intelligence is introduced, as some analogues of generations of technology.

New definition

Let's try to define intelligence more broadly.

Intelligence is an observable ability to solve problems posed to its carrier.

By virtue of its universality, such a definition allows one to break away from the usual idea of intelligence as an exclusive ability of a person and look at the world around from less anthropocentric positions.

In addition, the definition emphasizes the need to monitor this ability. We do not yet know how to measure the potential of intelligence. In science fiction works, often there is a certain device that immediately gives out a figure of intellectual potential. However, in the real world, in order to measure some aspect of intelligence, we use exams and tests consisting, in fact, of individual tasks, and during the test we observe and measure with grading points this very ability to solve them.

Individualization

Individualization was chosen as the main characteristic of the evolutionary level of intelligence (as an analogue of generation in technology). Judging by the comments on the first part of the article, this choice was puzzling.

But we are all well acquainted with individualization. When we choose clothes, which, like not everyone else, decorate ourselves or our car with baubles, we introduce a cozy originality into the decoration of our standardized dwelling - all this is a manifestation of our personality, a manifestation of the freedom of our inner world.

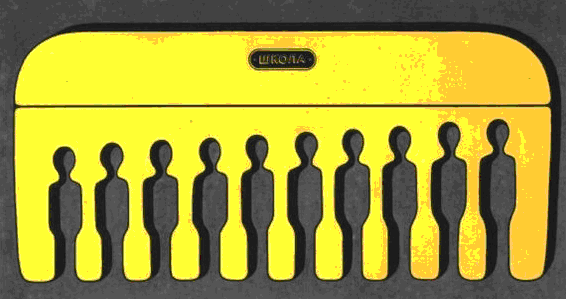

In sum, many individuals give wealth. The wealth of opinions, ideas, decisions, points of view, self-expression and, as a result, the intellectual wealth of us, as a people and as a whole biological species. And, on the contrary, the processes of unification of people, the desire to “cut to one comb”, “measure with one measure” are the modern synonyms of fooling, lack of intelligence.

But whether to be a unique person or to unify oneself, to be oneself or to be like everything in our time is still our personal choice. At least we are not structurally limited in this, and our intellect, the intellect of man, in its potential offers us infinite individual diversity.

Technically, at the other end of the individualization scale are algorithms. Different computers with the same program will always act in the same way. And, precisely because of its constructive nature, the intelligence of this class has zero individual diversity or zero level of individualization.

Intelligence on the Way to Mind

Let's try to figure out what evolutionary milestones are between zero and infinite individualization?

The first step is when each individual, the bearer of intelligence, solves problems in some different way, but the ways of these decisions [technically] are unchanged during the life of the individual. If we add here inheritance and selection, we get a very clear evolutionary mechanism, when unsuccessful and ineffective solutions will be eliminated, and successful and effective ones will be fixed. In nature, this is realized through unconditioned reflexes. We will call this intelligence level I individualization.

The second step is when the individual carrier of intelligence has [technical] ability to change the ways of solving problems. Now, the individual himself in the course of his life can choose more successful solutions and discard ineffective ones. In nature, this is realized through conditioned reflexes. It will be the intelligence of the II level of individualization.

The third step is when the individual carrier of intelligence has [technical] ability for coordinated collective action. Coordination of actions requires the development of conventional communication. Moreover, the communication channel can be very different: these are gestures, and sounds, and smells, and visual signals. The principal characteristic here is conventionality, that is, the signal values are not strictly predetermined by the algorithms, but are the result of an agreement local to a group of individuals. An important bonus of this level is the potential ability for interspecific communication. This is the intelligence of the III level of individualization.

The fourth step is the emergence of abstract logical thinking. As you know, thinking is based on the ability to communicate, because abstractly logically we think in words, that is, communicative units that become semantic. This is the IV level of individualization, or human intelligence. This level of intelligence is traditionally called the mind, and the person himself as a species - reasonable.

As we see, each step fundamentally expands the degree of individualization, gradually changing the potential ability of the value of this characteristic to vary from zero to infinity.

Robopsychology as it is

Thanks to the classification of the level of intelligence proposed above, we can more clearly imagine both ways to improve robots and their consequences.

If the evolution of intelligence is the path from lesser to more individualization, then this means the inevitability of the appearance of robots with individual behavior, which means that the question will inevitably arise how to control and regulate this behavior.

A robot cannot harm a person or, through inaction, allow a person to be harmed. (c) “3 laws of robotics”, A. Azimov, 1942

As we can see from the date of birth of the cited work, the question of controlling the behavior of robots has been of interest to humanity for more than a decade. In this case, the recognized classic of science fiction followed the traditional path of jurisprudence and himself in his works showed the futility of this option due to the ease of changing its interpretations.

The law that draws where he turned, and there came out (c) Folk wisdom

But if the option of restrictions using legal formulations is futile, then how to solve the problem of monitoring and regulating the behavior of the robot? Let's see how nature coped with this task. After all, starting from the second level of individualization, living things got the technical possibility of some freedom of their behavior. And what about the interests of one’s own security, survival and prosperity of one’s kind?

Nature solved this problem in a very interesting way. The strategic tasks of the individual remained hard-coded, and the tactical ones were handed over to changing individual behavior. Emotions became the intermediary between tactics and strategy. Each living individual, starting from the second level of individualization, received the ability to experience positive emotions when his behavior corresponded to strategic objectives and negative when contradicted. Moreover, emotions can both appear after the fact, after the decision is made, for example, as joy and glee from a successful salvation in a moment of danger, and precede and induce a decision, for example, anxiety during the rut.

Love dries a person. The bull moos with passion. The rooster finds no place for itself. The leader of the nobility loses his appetite. (c) 12 Chairs. Ilf and Petrov.

Can this decision be transferred to the field of robotics and similarly control the behavior of robots through motivation by emotions for action and an emotional reward for correct action and punishment for wrong? I guess it's yes. How exactly? This will be discussed in the sequel.

It is possible that if the robot experiences emotions, its behavior will be much closer and more understandable to us and we will be able to more easily include robots in the community of people.

Thanks and invitations

The author thanks Professor N.V. Khamitov for the invaluable help provided during the development of this theory.

The author invites everyone, and especially evolutionary biologists, to participate in the discussion, or maybe carried away, and join the work on the theory.