TL; DR : can Haiku get proper support for application packages, such as application directories (like .app on Mac) and / or application images (Linux AppImage )? It seems to me that this will be a worthy addition, which is easier to implement correctly than in other systems, since most of the infrastructure is already there.

A week ago, I discovered Haiku, an unexpectedly good system. Well, since I have long been interested in catalogs and application images (inspired by the simplicity of the Macintosh), it is not surprising that an idea came to my mind ...

For a complete understanding: I am the creator and author of AppImage, a Linux application distribution format aimed at the simplicity of the Mac and providing complete control to application authors and end users (want to know more - see the wiki and documentation ).

What if we do an AppImage for Haiku?

Let's think a little, purely theoretically: what needs to be done in order to get an AppImage , or something similar, on Haiku? It is not necessary to create something right now, because the system that is already in Haiku works amazingly, but an imaginary experiment would turn out to be nice. He also demonstrates the sophistication of Haiku, compared to Linux desktop environments where such things are terribly difficult (I have the right to say this: I've been debugging for 10 years now).

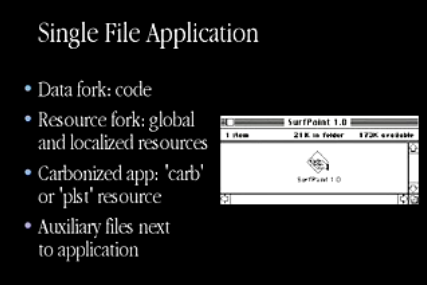

On Macintosh System 1, each application was a separate file, "managed" in the Finder. Using AppImage I try to recreate the same user experience on Linux.

First, what is AppImage? This is a system for releasing third-party applications (for example, Ultimaker Cura ), which allows you to release applications when and how they hunt: you don’t need to know the features of various distributions, build policies or build infrastructure, they do not need support from maintainers, and they do not indicate to users that (not) can be installed on computers. AppImage should be understood as something similar to a package for Mac in .app format inside a .dmg disk image. The main difference is that applications are not copied, but always remain inside AppImage, much like the Haiku .hpkg packages are installed, and are never installed in the usual sense.

For more than 10 years of its existence, AppImage gained some appeal and popularity: Linus Torvalds himself publicly approved it, and widespread projects (for example, LibreOffice, Krita, Inkscape, Scribus, ImageMagick) took it as the main way to distribute continuous or nightly assemblies, not interfering with installed or non-installed user applications. However, Linux desktops and distributions most often still cling to the traditional, centralized distribution model based on the maintainers and / or promote their own corporate business and / or engineering programs based on Flatpak (RedHat, Fedora, GNOME) and Snappy (Canonical, Ubuntu) . Comes to funny .

How does it work

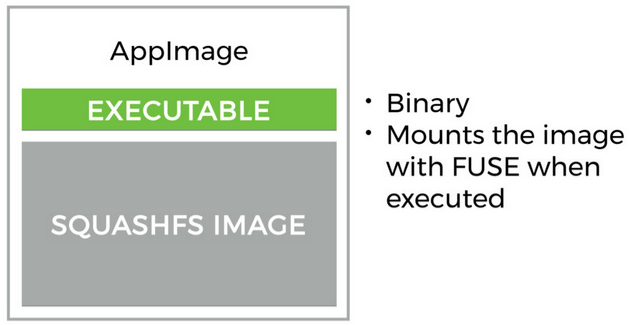

- Each AppImage contains 2 parts: a small double-click executable ELF (the so-called.

runtime.c ), followed by a SquashFS file system image.

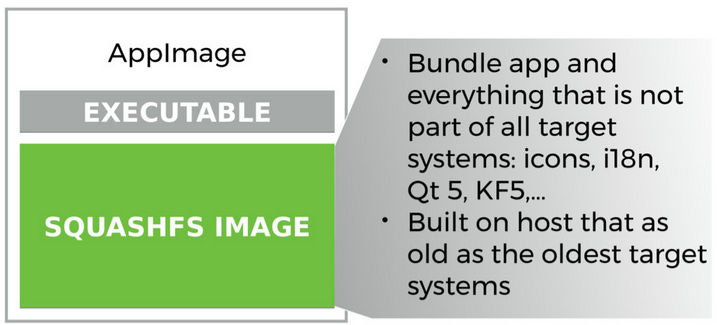

- The SquashFS file system contains a payload in the form of an application and everything you need to run it, which in your right mind cannot be considered part of the default installation for every fairly fresh target system (Linux distribution). It also contains metadata, for example, application name, icons, MIME types, etc., etc.

- When launched by the user, runtime uses FUSE and squashfuse to mount the file system, after which it processes the launch of some entry point (the so-called AppRun) inside the mounted AppImage.

The file system is unmounted after the process completes.

Everything seems to be simple.

And these things complicate things:

- with such a variety of Linux distributions, there is nothing “in their right mind” you can call “part of the default installation for every fresh target system”. We circumvent this problem by assembling an excludelist , which allows us to determine what will be packaged in AppImage and what needs to be taken somewhere else. At the same time, we sometimes miss, despite the fact that, in general, everything works fine. For this reason, we recommend that package creators check AppImages on all target systems (distributions).

- Applications in the form of a payload must be roaming around the file system. Unfortunately, in many applications absolute paths to, for example, resources in

/usr/share hard-coded. This needs to be fixed somehow. In addition, you must either export LD_LIBRARY_PATH , or fix rpath so that the loader can find related libraries. The first method has its drawbacks (which are bypassed in complex ways), and the second is simply cumbersome. - The biggest UX trap for users is to set the executable bit to the AppImage file after downloading. Believe it or not, for some it’s a real barrier. The need to set an executable bit is cumbersome even for advanced users. As a workaround, we proposed installing a small service that monitors AppImage files and sets the executable bit for them. In its pure form, not the best solution, because it will not work out of the box. Linux distributions do not deliver this service, therefore, out of the box users are all bad.

- Linux users expect the new application to have an icon in the launch menu. You won’t say to the system: “Look, there’s a new application, let's get started.” Instead, according to the XDG specification, you need to copy the

.desktop file to the desired location in /usr for system-wide installation, or in $HOME for individual installation. Icons of certain sizes, according to the specification XDG, you need to put it in certain places in usr or $HOME , then run the commands in the working environment to update the icon cache, or hope that the working environment manager will figure it out and automatically detect everything. Same as with MIME types. As a workaround, it offers To use the same service, which, in addition to setting the execution flag, will, if there are icons, etc. in AppImage, copy them from AppImage to the correct places according to the XDG, it will be supposed to clean up everything when deleting or moving it. Of course, there are differences in the behavior of each working environment, in graphic file formats, their sizes, storage locations and ways to update caches, which creates a problem. In short, this method is a crutch. - If the above is not enough, there is no AppImage icon in the file manager. In the Linux world, they still have not decided on the implementation of elficon (despite the discussion and implementation ), so it is impossible to embed the icon directly into the application. So it turns out that the applications in the file manager do not have their own icons (no difference, AppImage or something else), they are only in the start menu. As a workaround, we use thumbnails - a mechanism that was originally designed so that desktop managers can display thumbnails for previewing graphic files as their icons. Therefore, the service for setting the executable bit also works as a “miniaturizer”, creating and recording thumbnails of icons in the corresponding places

/usr and $HOME . This service also performs a cleanup if the AppImage is deleted or moved. Due to the fact that each desktop manager behaves a bit differently, for example, in what formats it accepts icons, in what sizes or places, this is all really painful. - The application simply crashes at runtime if errors occur (for example, there is a library that is not part of the base system and not supplied in AppImage), and no one tells the user in the GUI what exactly is happening. We started to work around this using notifications on the desktop, which means that we need to catch errors from the command line, convert them into user-understandable messages, which then still need to be displayed on the desktop. And of course, each working environment treats them a little differently.

- At the moment (September 2019, approx. Translator), I have not found a simple way to tell the system that the

1.png file 1.png be opened using Krita, and 2.png using GIMP.

The storage location for the cross-desktop specifications used by GNOME , KDE, and Xfce is freedesktop.org

Achieving a level of sophistication deeply woven into Haiku's work environment is difficult, if not impossible, because of the XDG specifications from freedesktop.org for cross-desktop, as well as implementations of desktop managers based on these specifications. As an example, we can cite one system-wide Firefox icon: apparently, the authors of XDG did not even think that the user can have several versions of the same application.

Icons of different versions of Firefox

I was wondering what the Linux world could learn from Mac OS X so as not to mess with system integration. If you have the time and you are doing this, be sure to read what Arno Gourdol, one of the first Mac OS X engineers said:

We wanted to install the application as easy as dragging the application icon from somewhere (server, external drive) onto the disk of your computer. To do this, all information is stored in the application package, including icons, version, file type being processed, type of URL schemes that the system must know to process the application. This also includes information for 'centralized storage' in the Icon Services and Launch Services database. To maintain performance, applications are 'discovered' in several 'well-known' places: in the system and user directory Applications, as well as in some others automatically if the user has moved to the Finder to the directory containing the application. In practice, this worked very well.

https://youtu.be/qQsnqWJ8D2c

Apple WWDC 2000 Session 144 - Mac OS X: Packaging Applications and Printing Documents.

There is nothing like this infrastructure on Linux desktops, so we are looking for workarounds around structural constraints in the AppImage project.

Is Haiku in a hurry to help?

And one more thing: Linux platforms as the basis of working environments, as a rule, are so unspecified that many things that are very simple in a consistent system with a full stack disappoint Linux fragmentation and complexity. I devoted a whole report to issues related to the Linux platform for working environments (knowledgeable developers have confirmed: everything will remain so for a very long time).

My report on Linux desktop environments in 2018

Even Linus Torvalds admitted that it was because of fragmentation that the idea of working environments failed.

Nice to see Haiku!

With Haiku, everything is amazingly simple.

Although the naive approach to porting AppImage to Haiku is to simply attempt to build (mainly runtime.c and service) its components (which may even be possible!), It will not bring much benefit to Haiku. Because in fact most of these problems have been resolved by Haiku and conceptually justified. Haiku provides exactly those bricks for the system infrastructure that I have been looking for in Linux desktop environments for so long and could not believe that they are not there. Namely:

Believe it or not, many Linux users cannot overcome this. At Haiku, everything is done automatically!

- ELF files that do not have an executable bit receive it automatically when you double-click in the file manager.

- Applications can have embedded resources, for example, icons that appear in the file manager. You do not need to copy a bunch of images to special icon directories, and therefore, you do not need to clean them after deleting or moving the application.

- There is a database for linking applications with documents, there is no need to copy any files for this.

- In the lib / directory next to the executable, libraries are searched by default.

- There are no numerous distributions and desktop environments, all that works - works everywhere.

- There is no separate startup module that differs from the Applications directory.

- Applications have no built-in absolute paths to their resources; there are special functions for determining the location at runtime.

- The idea of compressed file system images has been introduced: this is any hpkg package. All of them are mounted by the core.

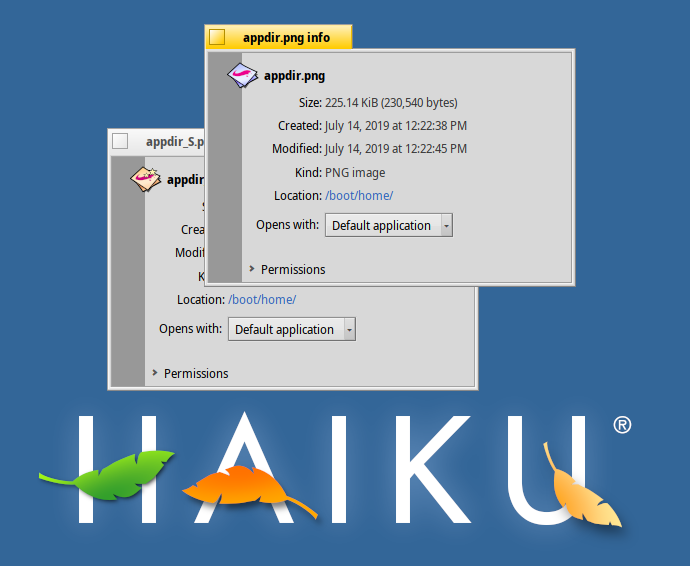

- Each file is opened by the application that created it, unless you explicitly specify something else. How awesome it is!

Two png files. Pay attention to different icons showing that they will be opened by different applications by double-clicking. Also pay attention to the drop-down menu "Open with:", where the user can select a separate application. How easy!

It looks like many of the crutches and workarounds needed by AppImage on Linux become unnecessary on Haiku, which is based on simplicity and sophistication, thanks to which it copes with most of our needs.

Do Haiku need application packages in the end?

This leads to a big question. If it would be an order of magnitude easier to create a system like AppImage on Haiku than on Linux, would it be worth it? Or has Haiku with its hpkg package system virtually eliminated the need to develop such an idea? Well, for the answer you need to look at the motivation for the existence of AppImages.

View from the user

Take a look at our end user:

- I want to install the application without asking for the administrator password (root). There is no administrator on Haiku, the user has full control, as this is a personal system! (In principle, you can imagine this in multi-user mode, I hope the developers will keep simplicity)

- I want to get the latest and best versions of applications, not to wait for them to appear in my distribution (most often it means "never", at least if you do not update the entire OS). At Haiku, this is "solved" with floating releases. This means that it is possible to get the latest and best versions of applications, but for this you need to constantly update the rest of the system, actually turning it into a "moving target" .

- I want several versions of the same application nearby, because you can’t find out what was broken in the latest version, or, for example, as a web developer, I need to check my work under different versions of the browser. Haiku solved the first, but not the second problem. Updates are rolled back, but only for the entire system, it is impossible (as I know) to launch, for example, several versions of WebPositive or LibreOffice at the same time.

One of the developers writes:

In essence, the rationale is this: the use case is so rare that optimization does not make sense to it; handling it as a special case at HaikuPorts seems more than acceptable.

- I need to save applications where I like, and not on the boot disk. I often run out of space on disks, so I need to connect an external drive or network directory to store applications (all versions that I downloaded). If I connect such a disk - it is necessary that the applications are launched by double-clicking. Haiku saves older versions of packages, but I don’t know how to move them to an external drive, or how to call applications from there later.

Developer Comment:

Technically, this is already possible with the mount command. Of course, we will make a GUI for this as soon as enough interested users are gathered.

- I don’t need millions of files scattered around the file system that I cannot manually manage myself. I want one file per application, which I can easily download, move, delete. On Haiku, this problem was solved with the help of

.hpkg packages, which transfer, for example python, from thousands of files to one. But if there is, for example, Scribus using python, then I have to deal with at least two files. And I have to take care to keep their versions working with each other.

Numerous versions of AppImages running side by side on a single Linux

View from the side of the application developer

Let's look from the perspective of an application developer:

- I want to manage the entire user experience. I don’t want to depend on the operating system, which will tell me when and how I should release applications. At Haiku, developers can work with their own hpkg repositories, but this means that users will need to manually configure them, which makes this idea less attractive.

- I have a download page on my website where I distribute

.exe for Windows, .dmg for Mac, and .AppImage for Linux. Or maybe I want to monetize access to this page, can it all be? What do I need to post there for Haiku? Enough .hpkg file with .hpkg dependencies only - My software needs certain versions of other software. For example, it’s known that Krita needs a fixed version of Qt, or Qt, that is fine-tuned to a specific version of Krita, at least until the corrections return back to Qt. You can pack your own Qt for the application in the

.hpkg package, but most likely this is not welcome.

Normal application download page. What to place here for Haiku?

Will bundles (existing as application directories like AppDir or .app in Apple style) and / or images (as heavily modified Apple's AppImages or .dmg ) be useful additions to the Haiku desktop? Or will it dilute the whole picture and lead to fragmentation, and therefore add complexity? I am torn: on the one hand, the beauty and sophistication of Haiku is based on the fact that there is usually one way to do something, not a lot. , / , , .

mr. waddlesplash

Linux ( , — . ) . Haiku .

?

...

, : — Haiku:

Haiku,

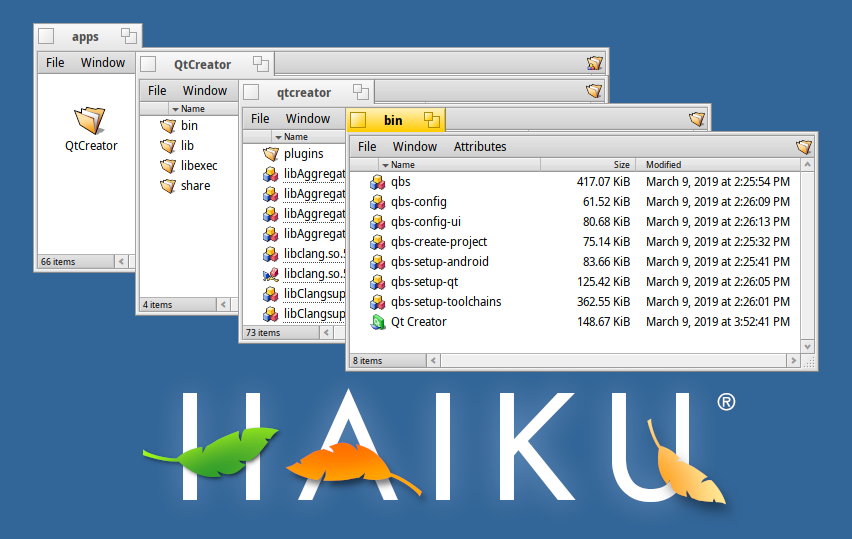

, , , Macintosh Finder. , QtCreator "QtCreator", ?

:

, , ? , - ?

Haiku, ? , .

mr. waddlesplash:

, : , , - . BeOS R5 Haiku — ...

!

Haiku?

hpkg, :

.hpkg- ( , )

.hpkg ( 80% ) - ,

.hpkg , ( , QtCreator): .hpkg , .

mr. waddlesplash :

, , — /system/apps , Deskbar , /system/apps , ( MacOS). Haiku , , , .

- Haiku , , , , " ", , ( 20% ).

.hpkg , , — . (, .hpkg , — , . ! — .) , .hpkg , , HaikuDepot… ).

mr. waddlesplash:

. "" pkgman .

hpkg, . , .

Conclusion

Haiku , , , Linux. .hpkg — , . , Haiku . — , Haiku, , . Haiku . , , , Haiku. , «-». 10 Linux, Haiku, , , . , , Haiku , , — . , , hpkg , . , Haiku , , ( ) "". , ?

Try it yourself! Haiku DVD USB, .

Have a question? telegram- .

: C C++. Haiku OS

: Haiku.

: