A translation of this article has been prepared specifically for students in the Java Developer course .

In my previous article

Everything About Method Overloading vs Method Overriding , we looked at the rules and differences between method overloading and overriding. In this article, we will see how method overloading and overriding are handled inside the JVM.

For example, take the classes from the previous article: the parent

Mammal (mammal) and the child

Human (human).

public class OverridingInternalExample { private static class Mammal { public void speak() { System.out.println("ohlllalalalalalaoaoaoa"); } } private static class Human extends Mammal { @Override public void speak() { System.out.println("Hello"); }

We can look at the question of polymorphism from two sides: from the “logical” and “physical”. Let's first look at the logical side of the issue.

Logical point of view

From a logical point of view, at the compilation stage, the called method is considered as belonging to the type of reference. But at run time, the method of the object referenced will be called.

For example, in the line

humanMammal.speak(); the compiler thinks that

Mammal.speak() will be called, since

humanMammal declared as

Mammal . But at run time, the JVM will know that

humanMammal contains a

Human object and will actually invoke the

Human.speak() method.

It's all pretty simple as long as we stay at a conceptual level. But how does the JVM handle this all internally? How does the JVM calculate which method should be called?

We also know that overloaded methods are not called polymorphic and resolve at compile time. Although sometimes method overloading is called

compile-time polymorphism or early / static binding .

Overridden methods (override) resolve at runtime because the compiler does not know if there are overridden methods in the object that is assigned to the link.

Physical point of view

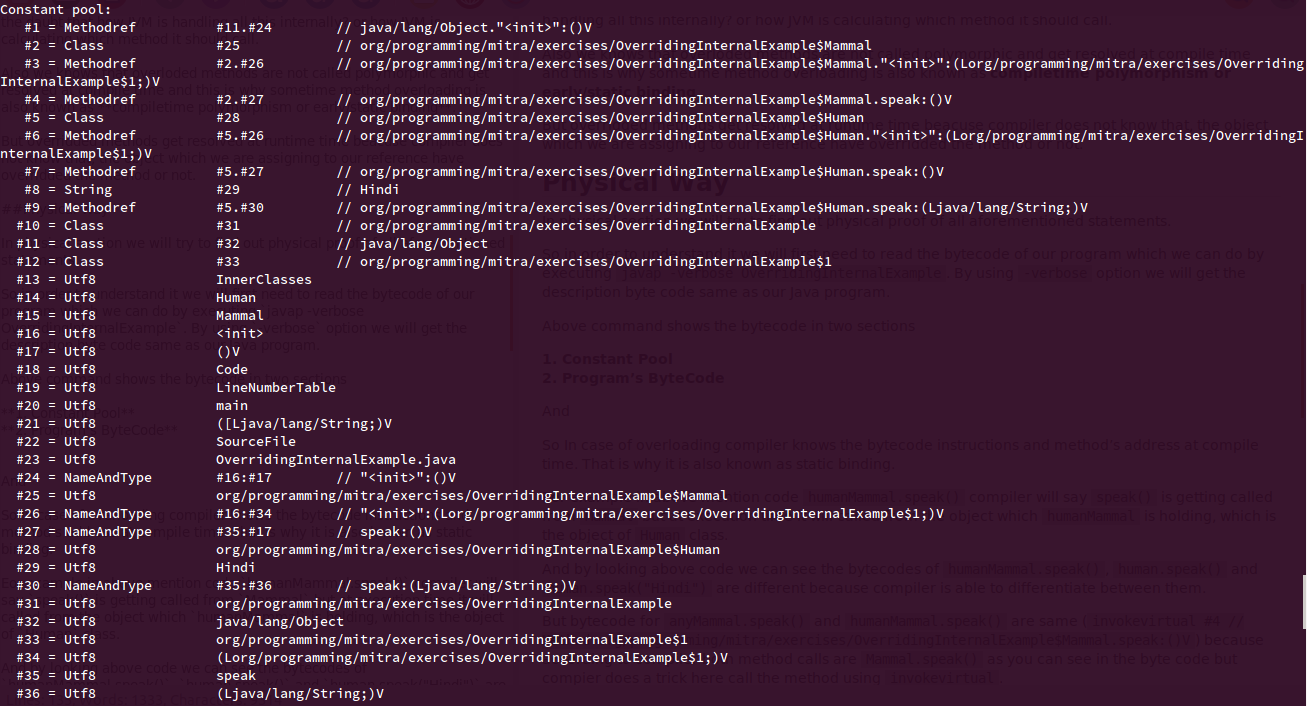

In this section, we will try to find “physical” evidence for all of the above statements. To do this, look at the bytecode that we can get by running

javap -verbose OverridingInternalExample . The

-verbose parameter will allow us to get a more intuitive bytecode corresponding to our java program.

The command above will show two sections of bytecode.

1. The pool of constants . It contains almost everything that is needed to run the program. For example, method references (

#Methodref ), classes (

#Class ), string literals (

#String ).

2. The bytecode of the program.

2. The bytecode of the program. Executable bytecode instructions.

Why method overloading is called static binding

In the above example, the compiler thinks that the

humanMammal.speak() method will be called from the

Mammal class, although at run time it will be called from the object referenced in

humanMammal - it will be an object of the

Human class.

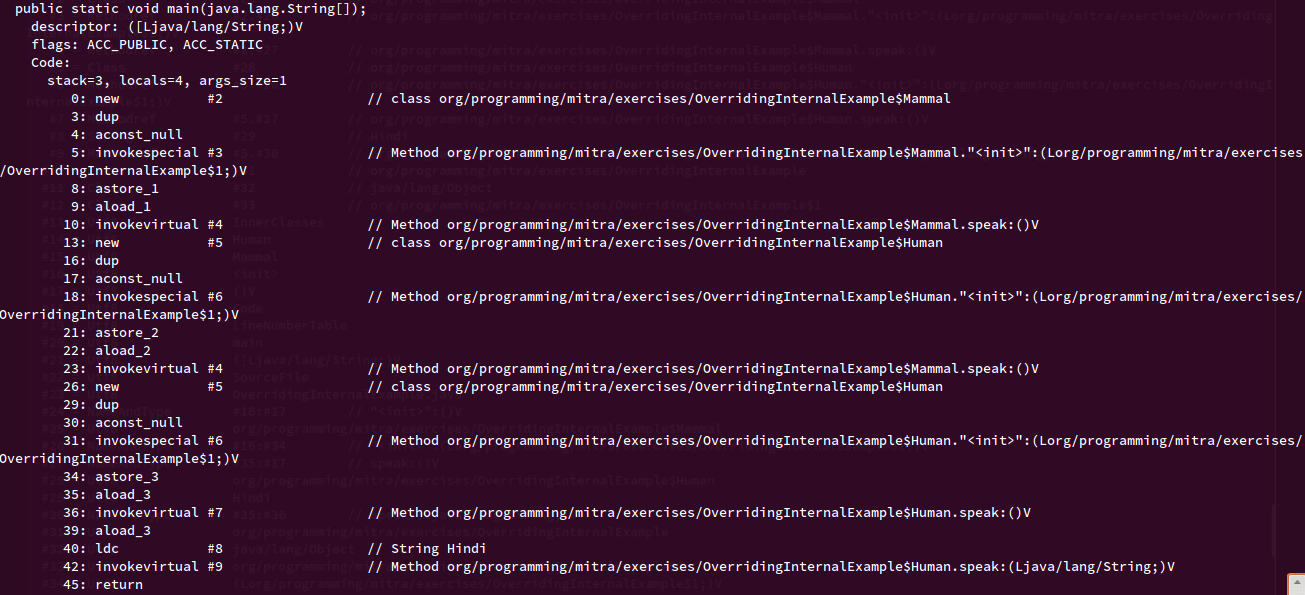

Looking at our code and the

javap result, we see that different bytecode is used to call the methods

humanMammal.speak() ,

human.speak() and

human.speak("Hindi") , since the compiler can distinguish them based on the class reference .

Thus, in the event of a method overload, the compiler is able to identify bytecode instructions and method addresses at compile time. That is why this is called

static linkage or compile-time polymorphism.Why method overriding is called dynamic binding

To call the

anyMammal.speak() and

humanMammal.speak() methods, the bytecode is the same, since from the point of view of the compiler both methods are called for the

Mammal class:

invokevirtual #4 // Method org/programming/mitra/exercises/OverridingInternalExample$Mammal.speak:()V

So now the question is, if both calls have the same bytecode, how does the JVM know which method to call?

The answer is hidden in the bytecode itself and in the

invokevirtual instruction. According to the JVM specification

(translator's note: reference to JVM spec 2.11.8 ) :

The invokevirtual instruction calls the instance method through dispatching on the (virtual) type of the object. This is the normal dispatch of methods in the Java programming language.

The JVM uses the

invokevirtual to invoke in Java methods equivalent to the C ++ virtual methods. In C ++, to override a method in another class, the method must be declared as virtual. But in Java, by default, all methods are virtual (except for final and static methods), so in the child class we can override any method.

The

invokevirtual instruction takes a pointer to the method to call (# 4 is the index in the constant pool).

invokevirtual #4

But reference # 4 further refers to another method and Class.

#4 = Methodref #2.#27

All these links are used together to get a reference to the method and the class in which the desired method is located. This is also mentioned in the JVM specification (

translator's note: reference to JVM spec 2.7 ):

The Java Virtual Machine does not require any specific internal structure of objects.

In some Oracle Virtual Machine Java implementations, a reference to a class instance is a reference to a handler, which itself consists of a pair of links: one points to a table of object methods and a pointer to a Class object representing the type of the object, and the other to the area data on the heap containing object data.

This means that each reference variable contains two hidden pointers:

- A pointer to a table that contains the methods of the object and a pointer to the

Class object, for example, [speak(), speak(String) Class object] - A pointer to memory on the heap allocated for object data, such as object field values.

But again the question arises: how does

invokevirtual work with this? Unfortunately, no one can answer this question, because it all depends on the implementation of the JVM and varies from JVM to JVM.

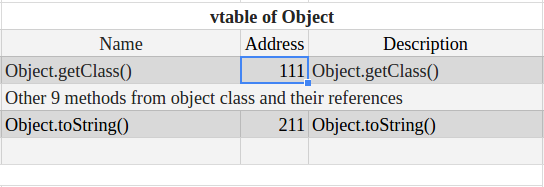

From the above reasoning, we can conclude that a reference to an object indirectly contains a link / pointer to a table that contains all the references to the methods of this object. Java borrowed this concept from C ++. This table is known by various names, such as

virtual method table (VMT), virtual function table (vftable), virtual table (vtable), dispatch table .

We cannot be sure how vtable is implemented in Java, because it depends on the specific JVM. But we can expect that the strategy will be about the same as in C ++, where vtable is an array-like structure that contains method names and their references. Whenever the JVM tries to execute a virtual method, it requests its address in the vtable.

For each class, there is only one vtable, which means that the table is unique and the same for all objects of the class, similar to the Class object. Class objects are discussed in more detail in the articles

Why an outer Java class can't be static and

Why Java is Purely Object-Oriented Language Or Why Not .

Thus, there is only one vtable for the

Object class, which contains all 11 methods (if

registerNatives not taken into account) and links corresponding to their implementation.

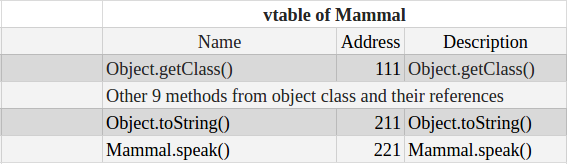

When the JVM loads the Mammal class into memory, it creates a

Class object for it and creates a vtable that contains all the methods from the vtable of the

Object class with the same references (since

Mammal does not override the methods from

Object ) and adds a new entry for the

speak() method.

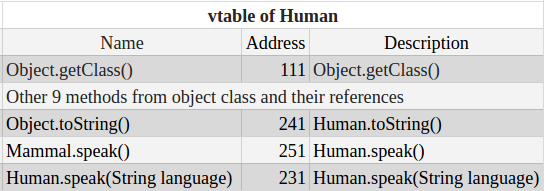

Then the class of the

Human class comes in, and the JVM copies all the entries from the vtable of the

Mammal class to the vtable of the

Human class and adds a new entry for the overloaded version of

speak(String) .

The JVM knows that the

Human class has overridden two methods:

toString() from

Object and

speak() from

Mammal . Now for these methods, instead of creating new records with updated links, the JVM will change the links to existing methods in the same index in which they were previously present, and retain the same method names.

The

invokevirtual instruction causes the JVM to process the value in the reference to method # 4 not as an address, but as the name of the method to be searched in the vtable for the current object.

I hope it’s now more clear how the JVM uses the constant pool and virtual method table to determine which method to call.

You can find the sample code in the

Github repository.