Last time,

Last time, we touched a little on the child’s egocentric position in preschool childhood. At one time, Jean Piaget put forward the thesis that a pre-school child, in principle, is characterized by egocentricity of thinking - that is, by default he believes that everything happens in the head of another person exactly the same as he does. Using a more modern term, Piaget believed that a preschooler does not have a theory of mind, and therefore is not able to take into account or accept someone else's point of view. In support of this, he cited the results of the following experiment:

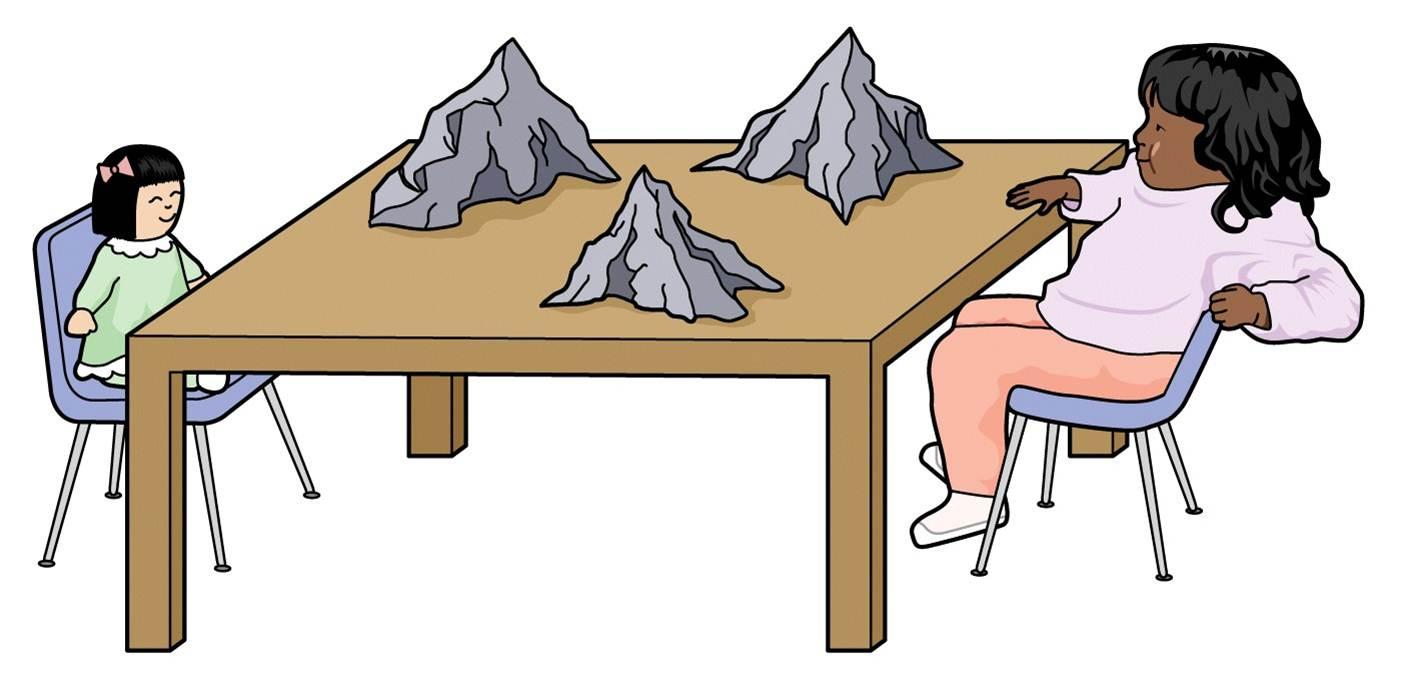

The child is presented with a model with three mountains. He has the opportunity to consider it from all sides. Then the child is put on a chair on one side of the model, on the other hand a doll is seated. The experimenter shows the child photographs of the layout in four different angles and asks what the doll sees.

Until about seven years, subjects in this experiment chose a picture with that angle that they themselves saw.

Subsequently, Jean Piaget was criticized a lot for how much he underestimated the possibilities of preschool children - and how much he overestimated the length of the period of egocentric thinking.

Where did this mistake come from?

Let's see what a child needs to correctly complete the three mountains task, in addition to the theory of the mind itself.

First, animation of the doll is involved in the formulation of the problem. About five years old, when the child has already formed a fairly clear idea of the real and imaginary (make-believe), he may refuse to answer the question in this wording, saying that the doll cannot see anything, because it is not alive, but a toy. And he will be right. We did not specify to him that we were studying the theory of the mind, and not the existence of common sense, and he could just in case demonstrate to him that he had common sense.

Secondly, to solve the problem, the child needs to mentally rotate a complex three-dimensional object. This is a task for visuospatial function, with a rather high level of complexity. At six years old, children often still have difficulty solving pentamino-shaped figures on a plane with their hands. And here we want to turn mentally and in space.

Thirdly - this is a non-trivial moment - in order to conceive mountains in general from the point of view of different angles, the child needs to be distracted from conceptual perception. By learning to label objects with words, the child mediates his perception with speech. The combination of colors and shapes in his mind immediately translates into words. (We do too.) If we give the child the task of drawing what he sees, then between his immediate perception and the drawing are words denoting those objects that he draws. Therefore, the child draws not what he sees, but what he knows. And almost any adult who has not specifically learned to draw does the same.

If we put a chair in front of the child in such a way that three of the four legs are visible, and ask him to draw what he sees, he will still draw four legs. Because between his impressions and the drawing is the word "chair", and he knows for sure that there are four legs in the chair. Hence the opposite perspective and other oddities of geometry in children's drawings - otherwise it often just doesn’t turn out to depict on the sheet plane everything that a child knows about a spatial object.

You can convey the idea of the angle to a six-year-old child and teach him to draw exactly what he sees, but it will be a difficult task that requires significant intellectual efforts from the child. By default, the preschooler is not able to take into account (and even realize) the angle. He will not be able to correctly answer the question of what the other sees, because at this time he is not able to reflect even his own visual perception!

If we ask a preschooler to sketch these three mountains, then he will draw not three partially overlapping triangles, but three triangles in a row - because his perception is mediated by the words “three mountains”, without specifying the relative position. Accordingly, in a classical experiment, a child can choose a picture similar to what he sees, simply because she undoubtedly depicts these same mountains (and not some others).

At this point, it should already be obvious that the statement of the problem is unsuccessful: it requires several complex things from the child at the same time, and we cannot understand the lack of any function that the child’s incorrect answer is associated with. Either he cannot take the point of view of the doll, or he cannot mentally turn the mountains, or the fact is that he immediately produces a text from the mountains, which does not have the “aspect” property by default.

And what will happen if we remove all that is superfluous from this task? I took a sheet of paper, painted a red circle on one side and a green circle on the other (the simplest form and the simplest colors that children should definitely recognize and name), and went through this sheet in kindergarten. I showed the sheet on both sides, then placed it between myself and the children and asked me to say which circle they see and which circle I see.

For three-year-olds, this task was unsolvable: they did not understand what the aunt with a piece of paper wanted from them, and just in case they were silent. One girl was able to understand the problem, but gave the wrong answer. However, one still cannot confidently say what the matter is: in the absence of a theory of mind, in the fact that there was not enough understanding of speech, in shyness in front of an unfamiliar adult, or in something else. Move on.

At four-year-olds, opinions were divided exactly in half: half of the group gave the correct answer, and half suggested that I see the same thing as them. Here the picture becomes clearer: if opinions are divided, then the function is at the formation stage at this time, and someone has already acquired it, while someone else has not.

Five-year-olds are already confidently giving the correct answer. This means that by the age of five, the child understands for sure that another person’s head may not have the same thing as his own. This is in line with the modern idea that the theory of mind is formed in 4-5 years.

But will a five year old child demonstrate a theory of mind? This is a separate issue. I go to five-year plans once again - now with a toy. In front of the eyes of the children and the teacher, I put the toy in a prominent place. Then I ask the teacher to go out, I hide the toy under the bed and ask:

- Where will your teacher look for a toy when she returns?

- Under the bed! - confidently answer the children.

Here it would be necessary to conclude that they do not have a theory of mind, if we had not just found out what it is. I ask the following question:

“Does she know where I hid the toy?”

- No! - children also answer with confidence.

Oh pa This means that there is a theory of mind, but they still can not use it in the conclusion, because they can not build the conclusion itself. I ask one more question:

“And if she does not know where I hid the toy, then where will she look for her?”

- Everywhere!

Bingo. They themselves are not yet building a conclusion, but in a Socratic dialogue they reach the right thought. This means that the task is available in the zone of proximal development: it’s not yet on its own, but already with support. And what will happen in a year? I go to six years old, I repeat the same procedure.

- Where will your teacher look for a toy when she returns?

- Everywhere! Behind the curtain! In the drawers! Under the beds!

(We start the teacher back into the room, and the teacher, to the indescribable delight of the children, in full accordance with their prediction, is looking for a toy everywhere.)

We conclude: by the age of six, a child can not only understand that the knowledge of another person is different from his own, but also predict his behavior based on this understanding.

Will the child take into account the desires of other people in his behavior, recognizing that they are different from his own, this, of course, is another separate question - the value system is already connected here (is this person important to me, is it ready for me to abandon my desires?).

Another separate question is whether it is possible to play open-ended with six-year-olds. This mechanics itself, it would seem, should already be understandable and accessible. In fact, some of the children are so worried about the fact that the enemy has a secret that they cannot continue the game until they look at the cards of their neighbor (they are tearing them out of curiosity, so it's impossible to think about anything else). This already involves self-control at the level of controlling emotions and excitability as a property of temperament. Another part of the children, in principle, does not understand why to hide their cards or chips. At the level of thinking, they still don’t have access to independent miscalculation of tactics taking into account the capabilities of the enemy (because almost all the computing power is spent on making a move in accordance with the rules), and accordingly, knowledge of what the opponent has in his hand practically does not affect the probability winnings.

So, we see that an ill-conceived experiment gave an error of at least 2-3 years in the periodization of development. At least - because according to some data, the theory of the mind is formed earlier, and under certain conditions its presence can be registered already in three years. And here we come to the problem of research in psychology in general: it is very difficult to set the task in such a way as to isolate the work of one function from the influence of a number of other factors (or at least control this effect). Therefore, for example, we still do not know how to assess the capabilities of autistic children. It is unclear how to determine why the child does not fulfill the task assigned to them: because he cannot or because he does not want, because we are not at all interested in his tasks and he does not want to interact with us?

With periodizations of child development in general, this problem is also present. Collecting data on children from a certain cultural environment, we know that at what age they begin to do, but it is often difficult to understand whether this is due to the fact that by this age the brain matures to perform certain functions - or because the children of this ages receive a certain experience and are subject to certain pedagogical influences. And for this, by the way, they also criticized the French classic - he described the periods of development of the child as a kind of automatic process, independent of the environment, although in reality there is a large share of cultural conditioning. That is, in fact, these are not periods of development of children in general, but periods of development of children studying under a certain educational program.

Similarly, about most of the standards of child development that we will operate with here, we must bear in mind that this is the average development path of an urban child who, from the age of three, goes through a standard domestic educational program and plays toys traditional for our culture (pyramids, cubes and so on). If the child has a different development environment, then it is expected that the development path will be different.